“Logic, emotion, credibility: these old-fashioned notions of persuasion take a back seat to the mere attention given to an interface itself. A person, organization, or institution can make their digital interface and prose style flatter the audience’s attention with the primary goal of creating a cool place to inhabit. This sense of a cool place is not only the main goal; a site can bank on coolness as the best bet at persuasion towards their goals.”

The interface rules. By appealing to the narcissism right behind the surface, an interface can hook users. If it is sticky, this is even better. Locking the user down and appearing to be cool is all that is needed to maintain the user’s attention. Just be cool. Everyone be cool.

“If there are any threads that run through the ever-changing notion of cool, they may be narcissism, ironic detachment, and hedonism in the name of a private rebellion that constantly accounts for its place within the social.”

We want what we want. If we can get it through a cool site, cool. If not, well, there are other places we can go for what we want. And what we want is ever changing. Give it to us now, or we go somewhere else for what we want. And we do want it. Now.

“Cool is the negotiating process of constantly heralding one’s individuality but only by comparing one’s self to both similarly and dissimilarly minded people (all the while acting like none of your actions matter that much or will have any intended effects beyond the individual ). The contradiction, of course, is that one’s sense of cool must necessarily come from other people despite cool’s focus on private rebellion. This is why it’s not so cool to define cool. Cool’s contradictions are socially useful ones and a deep analysis of its workings betrays the value of detached impassivity.”

Cool is a performance, man. We shout and yell at times, yeah, but it’s all part of the act that is our cool, our motion. Don’t harsh our cool and we won’t harsh yours, you know? We just want to be left alone. Unless we don’t. And then we do. You know? It’s all an act, man, just get on the stage with us and all.

“Itutu has a strong focus on helping others and lacks the hedonistic pleasures that mark today’s cool; nonetheless, the focus on presenting a calm and secure self in the face of adversity could be a foundation for cool.”

“Pountain and Robins (2000) argued that “one way this nihilism expressed itself was through the cultivation of revenge fantasies” (p. 99). If large scale political action wasn’t possible, then individuals like Taxi Driver‘s Travis Bickle or Dirty Harry‘s Harry Callahan could coolly (violently) take the law into their own hands (giving an interesting new spin to cool’s brand of individual defiance).

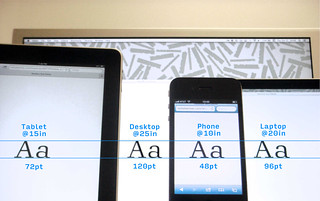

“Rice works from Gregory Ulmer’s critique of the topoi as serving print culture’s need for expectation and fixed–places of argument (paragraphs, tables, footnotes, etc.). He adopts chora (originally from Plato) to update the topoi for a digital age where “choral writing organizes any manner of information by means of the writer’s specific position in the time and space of culture” (Ulmer, 1994, p. 33).”

Tables? Paragraphs? Footnotes? Style and markup.

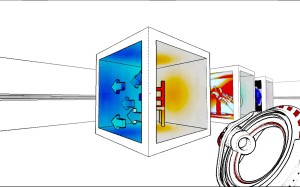

“Juxtaposition takes potential meanings of individual signifiers and forces us to fashion new meanings from viewing them in close proximity. Juxtaposition is the cool rebellion against normalized meaning in favor of the often concealed intentions of a composer and the preferred interpretations of the individual subject.”

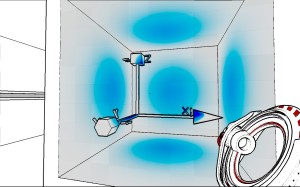

“Information is subjectively observed difference amongst a sea of potential sameness that causes the observer to note relevance or application. This highlights the importance of subjectivity to information; it’s not information if it makes no difference to the observer. Further, this implies that information is never static or pre-defined.”

So writes Hayles, too.

“Remember, as Shannon (Shannon & Weaver, 1949) suggested, information is not about meaning; rather, information is primarily concerned with the mere possibility of selection from choices.”

Comments:

Chvonne’s “Reading, Thinking, & Reflecting 11/10 (link)

I could definitely relate to the point she made about how Pepper’s approach to writing about cool was one the best ways to do it. Trying to walk the path of being academic without seemingly writing or speaking down to people who aren’t is one I take pretty often. Especially within the indie game dev scene, this can mean the difference between being “real” or seemingly like you are trying to crash into the scene without taking the time to prove yourself. (It’s a very product-focused scene. You have to show you can make interesting games, even if they aren’t always finished or polished.)

Summer’s “Lighting Up Classical Rhet_Reading notes for November 10th” (link)

But, on a more serious note, I think leaning towards a “cool threshold” is something to consider. About how trying for the cool-factor, as Pepper highlights from the thetruth site, can actually hurt the overall message in different ways.