How We Became Posthuman — Presentation from Dan Cox on Vimeo.

Key Terms and Concepts

Autonomy: The property of a system describing its ability to exercise agency within a context.

Autopoiesis: The description of a system capable of maintaining and reproducing itself; informationally closed.

Embodiment: Tangibility made manifest; Hayles relates it as “the specific instantiation generated from the noise of difference” (196).

Emergence: In regard to understanding system behaviors, it is the rise of greater complexity of pattern variability than was expected or anticipated.

Homeostasis: The property of a system describing its ability to maintain its internal consistency without or despite outside conditions changing.

Reflexivity: “the movement where that which has been used to generate a system is made, through a changed perspective, to become part of the system it generates” (8).

Materiality: An emphasis on the embodiment or other perceived physicality of an object or system.

Summary

Science fiction has fooled us, starts Hayles. Through things like Star Trek’s transporter and any number of other fictional technologies, we have been trained to think about the body and mind as separate things. That we can somehow upload our minds into computers or download our consciousness into robotic bodies. And that we can easily split the two and have our same self with our same embodiment.

This simply isn’t true, explains Hayles. “Information has lost its body,” she writes in regard to this issue (3). By dreaming of cyborgs and giving into Cartesian arguments, we risk forgetting about our bodies and the materially that makes us, us. It is the result of years of science fiction, some social studies, and the unfortunate influence of cybernetics. It has lead, relates Hayles in the introduction to How We Became Posthuman to be dangerously close to the idea that the body might only be a “fashion accessory” to be cast aside (5).

To understand how we have reached this point, Hayles tracks three primary ideas across time: homeostasis, reflexivity, and emergence. Each of which, she explains, arose through a confluence of the study of cybernetics, the ideas caught and proliferated by the public, and how those same ideas came to be incorporated in different ways as part of frameworks and literary movements. Each is a thread of the fabric that makes up how posthumans have come to be known, and how they might be known in the future.

The first, homeostasis, was a concern of many early cyberneticists. In trying to understand how machines might be considered alive, they tried to create a framework that included the ability for machines to maintain themselves. Thinking primarily through analog circuits and machinery, they positioned definitions that included homeostasis as a key building block for considering intelligence for both living entities and those machines that might be considered alive in some sense in the future.

It was within this thinking of systems maintaining themselves that the idea of neural nets and mapping organic synapses to circuits became a major emphasis. Neural nets, a metaphorical model of logical gates, gained great popularity as an easy way to think about the input, processing, and output of processes, leading a mathematical clarity to how to conceive of systems as a whole. However, in thinking about information itself as input to these systems, the importance of a context for information began to slip away.

It was Norbert Weiner who helped moved information away from raw data into a probabilistic function. Information became a way to discern pattern in the universe, true, but it was also now the output of some function, not a clear and separate entity in itself. By using neural nets, information could be reduced to only the probability of a pattern in comparing noise to some assumed signal.

Around this time, the second major thread also came into play. Reflexivity, the change of something used to generate a system as then a part of it, became central to understanding systems. Instead of simply looking at if a system could maintain itself, and what that might be said about living systems in turn, the emphasis turned to consider what observers of a systems might be doing to it. Even by looking at it, became the new model, an observer changes things. From the expectations of how a system should be working to just simply affecting a simulation by their presence, scientists shifted to consider what they themselves were doing to models and simulations. Were they, in other words, reflexively part of the understanding of systems they themselves were observing?

This move to reflexivity came as part of a major shift away from the early work with homeostasis, too. In summarizing how reflexivity was first thought about, Hayles writes that it was “constructed as neurosis” in early models around system behaviors (65). In fact, the threat of dissolving boundaries between systems and their observers (in trying to locate an individual’s subject position), was described by Hayles as the potential in some eyes of “[annihilating] the liberal subject as the locus of control” (110). Many scientists were deeply worried that a move to merge the connection between observer and system would completely erase the observer’s agency.

However, it was through writers like Donna Haraway that the cyborg intentions of this reflexivity gained a greater acceptance. It was not, as Haraway saw it, a move to collapse the agency of the observer, but a progression towards understanding the subject position of living systems as always mixed, always part machine and human. This was not a slice, but a splice, an overlapping space between systems that enabled a greater depth of understanding of both, not an abandonment of one or the other (116).

Furthering this move was Humberto Maturana and the concept of autopoiesis through reflexivity: “everything said is said by an observer” (135). Moving even more away from homeostasis, Hayles explains that Maturana saw reality constructed “through interactive processes determined solely by the organism’s own organization” (136). Even the illusion of some structure was merely “the particular instantiation that a composite unity enacts at a particular moment” (138). Everything was based in this understanding of autopoiesis and the coupling of systems to their contexts, linking systems to each other as well.

The final major thread, emergence, is a convergence of three different approaches to understanding system behavior: wetware, artificial biological life; hardware, robots and other embodied life forms; and software, programs created to be emergent or evolutionary. Primarily, the study of emergence in regard to systems comes from an application of biological metaphors to different systems (225). It is also what generally research into Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Artificial Life (AL) belongs, both vying to create life through different ways through machines.

It is also through both reflexivity and emergence, that theories arose to connect living and machine system. Processing information, a function of both, became a leading way to conceptualize how systems act (239). In some extreme versions of this application, however, the universe itself can even be broken down into an information processing unit, with different systems like humans merely interlocking parts of this one large system. Hayles even warns against this threat, writing that this “computational universe” model “becomes dangerous when it goes from being a useful heuristic to an ideology that privileges information over everything else” (244).

Hayles closes How We Became Posthuman by connecting the threads of homeostasis, reflexivity, and emergence back to re-inscribing information to its body, to restoring materiality. She states very simply that “Humans may enter into symbolic relationships with intelligent machines . . . they may be displaced by intelligent machines . . . but there is a limit to how seamlessly humans can be articulated with intelligent machines, which remains distinctively different from humans in their embodiments” (284). We cannot escape our embodiment because “culture not only flows from the environment into the body but also emanates from the body into the environment” (200). For no matter how much we may dream of transporters, robot bodies, and other science fiction fantasies, we cannot achieve them, not in the way they are presented right now.

Absence/Presence Continuum

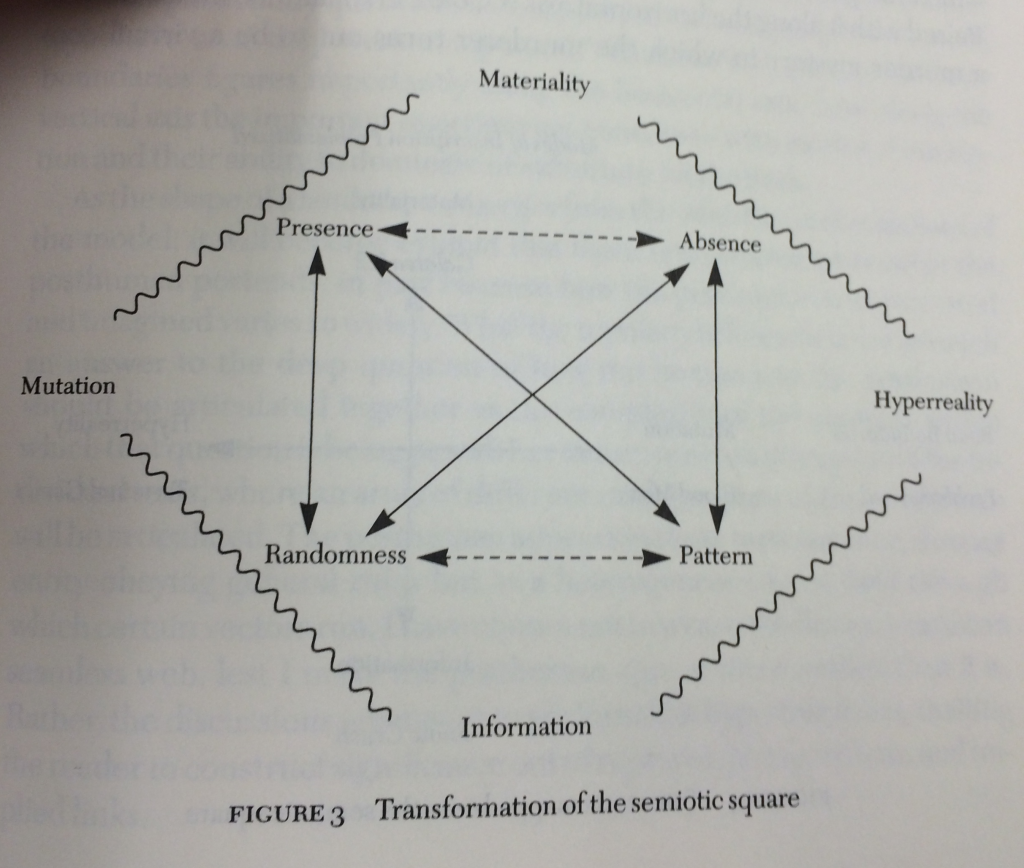

Hayles emphasis on the pattern-randomness continuum is her augmentation to the more common presence-absence configuration used in new media theory. Connecting specifically to this, Brooke notes in Lingua Fracta how Hayles adds an additional axis to this arrangement, plotting terms between both presence-absence and pattern-randomness.

Notably, Hayles positions Materiality at the intersection of presence and absence, making explicit the connection between embodiment and the push-pull relationship between communication and remediation practices through different mediums. She also places Information between the points of Pattern and Randomness, showing its relationship to discerning noise from signal and the interplay of both terms in trying to merge both a probabilistic view of information with its sister theory of information processing being the foundation of a universal view of the cosmos.

Embodiment in New Media

While Hayles does not deal explicitly with the terms “media” or even “multimodal,” she does make the more general case of re-inscribing embodiment into the process of realizing the relationship between living and artificial systems. For whatever the process involving technology, she asserts that they coexist in a useful symbiosis that does not see either absorbed into the other. Instead, there should be a understanding that each system is both itself and exists as overlapping with another.

Hayles also states very clearly that “information must always be instantiated in a medium” (13; original emphasis). Information is not free-floating, but is contained within some context. And it is in positioning both the information and its situational context that helps to develop the fuller picture of the content. For as important as the mind is to parsing content in a Descartian sense, the “murmurs of the body” (emotions, feelings) are equal in the cognition of information; they are joined and cannot be separated without fundamentally changing both.

Hi Dan,

I am sure that Haraway’s How We Became Posthuman would have been over my head had this been my canonical text and I am not sure how to reconcile the mind/body split as described in your presentation and in countless sci fi movies (yay). You presented the major issues within the text in a clear way that I could connect to my canonical text, Remediation, and precious coursework in rhetoric. It is helpful to see the connection to Plato, especially considering that mediation is central to balancing abstraction and multiplicity. I appreciated the challenge of discerning autopoietic in terms of your text, as that term was unfamiliar to me.

Good presentation, Dan. How do you think this text intersects with Haraway’s text? I like the cyborg motif. When working on the Haraway presentation, Sarah Carter and I developed this understanding that we are cyborg’s because we are so attached to our chosen technologies. How do you think this notion plays into Hayles’ work? If the mind and the body cannot be separated without a loss of information, what does it mean when our technologies become *part* of us?